One of the nice things about being an MD-PhD student at a research institution with a large academic medical center is that you tend to have a lot of support when it comes to working on your biomedical research questions. Despite institutional support, data can be a challenge and finding the right data for your question depends a lot on your connections with the myriad various data systems and data-gate-keepers that exist in your academic environment. Having done this data sleuthing for a decade plus I have bit of experience in ferreting out interesting sources of healthcare data.

One of my favorite data finds of all time was from a project I led when I was just starting out as quality improvement engineering for a hospital. I had been tasked with redesigning the inpatient rooms of the academic medical center I was working for. A significant portion of the project was blue-sky/brainstorming type engineering. But there was a portion of the project that involved troubleshooting the layout of an existing unit that had been receiving lots of complaints from nurses and CRNAs.

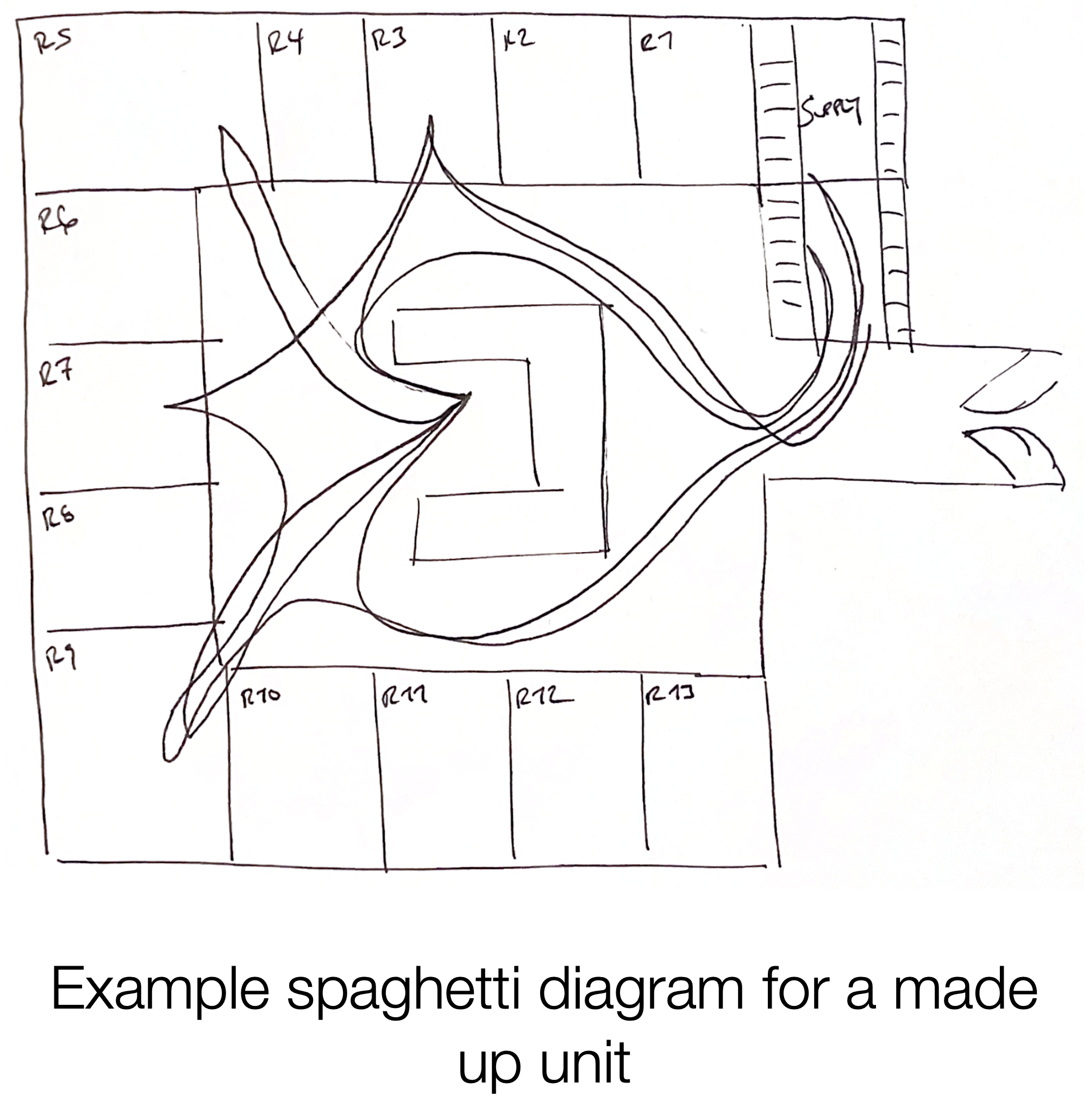

In order to benchmark the current unit and to help inform planned changes we needed to understand the flow of work done by the nursing staff. Our typical approach for this type of data collection was to collect spaghetti diagrams. A spaghetti diagram is a simple, but effective, chart that maps the travel path of a person or an object over a given duration. [1] When complete the travel path looks like a plate of spaghetti has been spilled on a floor plan. Making spaghetti diagrams is a time consuming process, as you need an observer to track the target person (in our case nurses or CRNAs) for long periods of time. After drawing the short-straw I found myself on the night shift shadowing the superb night team of the unit.

Halfway through my night shift I started wondering if there was a better way to be collecting this information. What we really were after was how often do the nurses need to leave a patient’s room because they are missing supplies and how long does this take them? Was there another way to collect this data without having to sacrifice sleep and (more importantly) not bothering nurses and patients?

I noticed that every time the nurse I shadowed entered a patient’s room there was a light above the patient’s room that lit up. When they left the room the light went dark. I inquired about the lights and learned from the nurse that I was shadowing that they were part of the nurse call light system, which is a like a souped up airplane flight attendant call light system. [2] In addition to indicating if a patient had a request it had the capability to show the presence of a nurse in a room. Additionally, I learned that this system was all wired up such that the unit coordinator (front desk of the unit) was the person that received the patient request calls and they also had a light board representing the status of the whole unit so that they could coordinate requests with nursing staff.

So, what initially seemed like a simple light switch turned out to be fairly complicated system. I figured that there must be a computer system facilitating this complexity. And if there was a computer involved in exchanging data then there was a chance it might also be storing data. And if I could get access to this data I might be able to answer my unit redesign questions without having to pull too many more night shifts. And I might be able to avoid bothering nurses and patients.

After leaving my shift with a stack of scribbles I emailed my supervisor inquiring about the call light system. She did a bit of hunting and found the people responsible for the call light system. After meeting with them we found out that the system did store data and that we could use it for our project, if we agreed to certain (very reasonable) terms of use.

We got the data. It was in the form of logs recording every timestamp a staff ID badge entered a different room. I whipped up a java program to analyze the amount of time nursing staff were in a patient’s room and the number of times they had to bounce between patient rooms and the supply rooms. It turns out the unit we were studying did have a problem with staff needing to leave the room frequently and rooms in that unit were slotted to be remodeled with more storage.

My big takeaway from this experience is that there’s alway a chance that there’s a good dataset that exists, but you won’t get access to it if you don’t do the work to look for it. And sometimes doing that work is easier than doing the work to collect your own data. :)

Erkin

Go ÖN Home

P.S. I started this post with some notes on gaining access to the typical datastore in academic medical settings. I have some additional thought about these data systems (e.g., discussing how they are typically structured and some of the things to look out for when using them) if you’re interested let me know and I’ll prioritize writing that up for a future post.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Zoey Chopra for catching a redundant paragraph.

Bibliography

-

What is a Spaghetti Diagram, Chart or Map? ASQ. 2022; Available from: https://asq.org/quality-resources/spaghetti-diagram. -

NaviCare⢠Nurse Call hill-rom.com. 2022; Available from: https://www.hill-rom.com/international/Products/Products-by-Category/clinical-workflow-solutions/NaviCare-Nurse-Call/.