This a foundational post that has two aims. The first is to demystify machine learning which I believe is key to enabling physicians and other clinicians to become empowered users of the machine learning tools they use. There’s a bit of ground I want to cover, so this post will be broken into several parts. This part situates and introduces machine learning then discusses the important components of machine learning models.

An Introduction

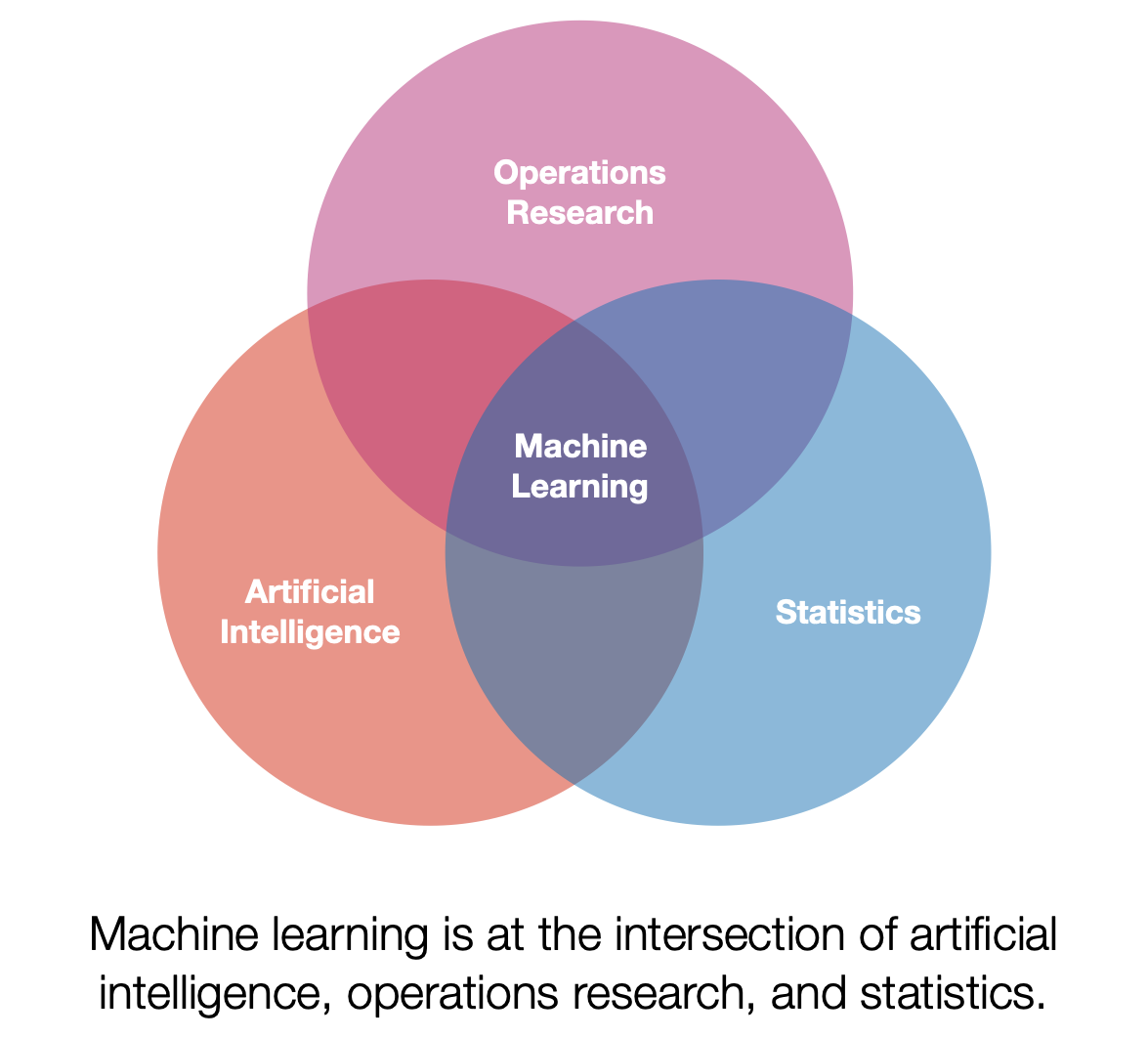

First a note on terminology. Machine learning (ML) can mean a lot of different things depending on who you ask. I personally view ML as a subset of artificial intelligence that has a strong focus on using data to build models. Additionally, ML has significant overlaps with operations research and statistics. One of my favorite definitions of ML models is presented by Tom Mitchell. [1] Paraphrased below:

A model is said to learn from experience if its performance at a task improves with experience. Quick note, the term model will be more fully explained below.

This set up lends itself well to analogy. One potential analogy is that of a small child learning how to stack blocks. The child may start from a point where it is unable to stack blocks, it will repeatedly attempt stacking, and eventually will master how to stack blocks in various situations. In this analogy stacking blocks is the task, the repeated attempts at stacking is the experience, and the performance is some criteria the child uses to assess how well they are stacking (e.g., height or stability).

We will now discuss this general definition for the specific use case of ML for healthcare. To contextualize this discussion we will focus on the ML model types that are most widely used in healthcare, supervised offline learning.1 Let’s break it down bit by bit. First, supervised learning constrains the learning process by introducing supervisory information, this information can be thought of as a teacher that tells the model if they got the task correct. This is very useful when trying to evaluate the performance of the model. In addition to being supervised the models used for healthcare are often developed in an offline setting. Offline describes the manner in which the model gains experience. Instead of learning from direct interaction with their environment they gain their experience by using information that has already been collected.

What is an ML model?

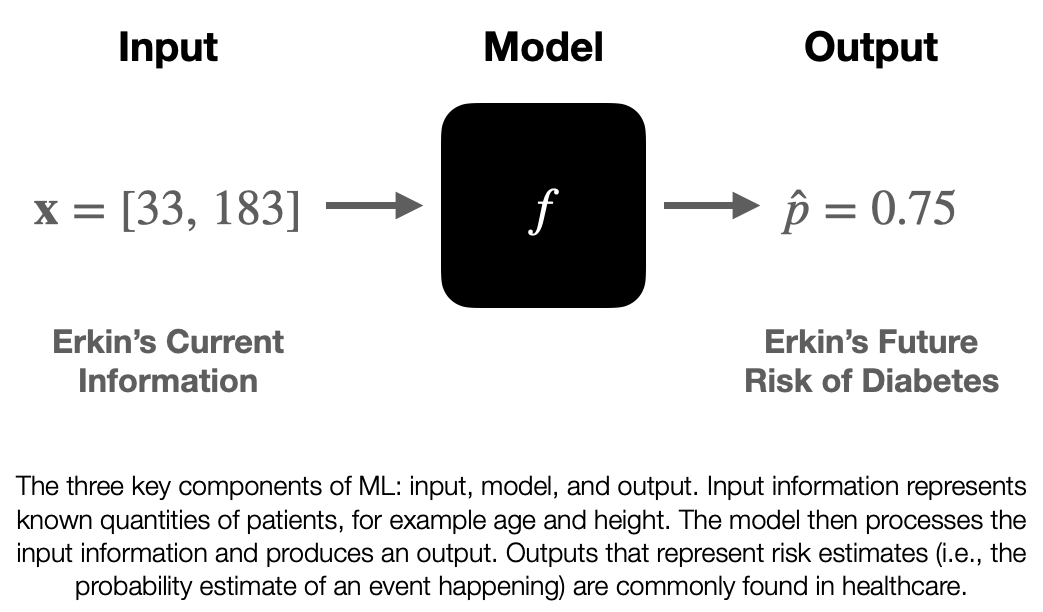

We’ve been talking about the concept of the model pretty abstractly, so let’s nail it down now. A model is a mathematical function, f, that operates on information, taking in input information and returning output information. This function f is the thing that “learns from experience”, however in our case the function has stopped learning by the time it is ready to be used. So when it is implemented in an EHR system f is usually fixed. We will discuss how f is created in the next blog post, but for now let’s treat it like a black box and discuss the information it interacts with.

The input information is known as x. Unlike the x you were introduced to in algebra class it actually represents information that we know. This information can take different forms depending on what information represents, but it is common to see x represent a list (or vector) of numbers. For example, if we wanted to give a model my age and height as input information you could set x=[33, 183], where 33 is my age in years and 183 is my height in centimeters.

The output of a model may vary based on use-case and may be a little opaque. I’ll present my notation (which may differ from what you see elsewhere), I believe this is notation is the easiest to understand. In healthcare we are often interested in risk stratification models that output risk estimates, denoted as (pronounced: p-hat). Risk estimates are estimates of the probability that an event will happen to a given patient. Let’s say we have a model that can assess a patient’s risk of developing diabetes in the next decade. If given information about me the model returns a

we could then say that the model estimates my risk of developing diabetes in the next decade as 75%. Ultimately should be a value between 0 and 1. By returning a numerical value along a continuous scale this is a type of regression (just like linear regression from high school statistics).

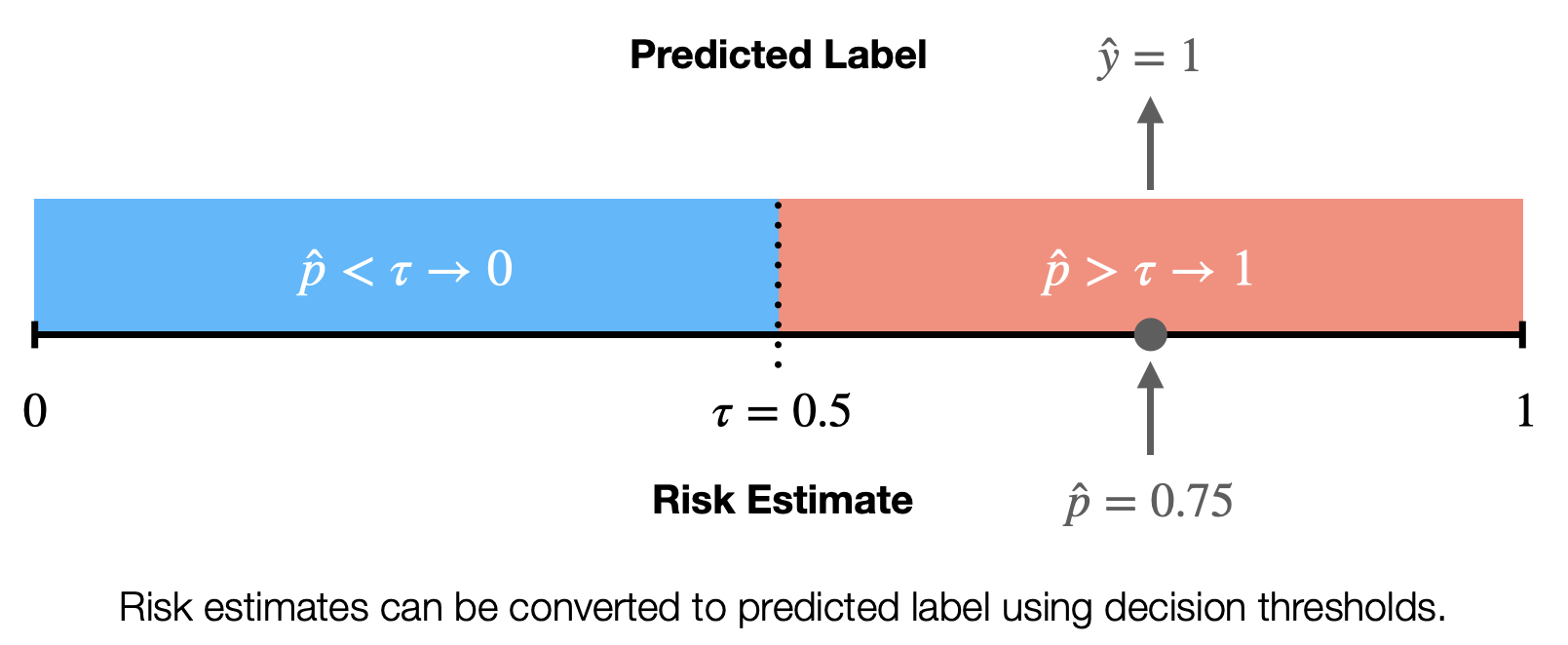

Sometimes we want to use models to separate out different populations of patients, for example to tell us if a patient belongs to the high-risk or low-risk group. When we use the model to return this information we call that output the predicted label. We denote predicted labels as (y-hat). We will loop back on a discussion of labels, but for now you can think of them as a model assigned group. This is a type of classification, specifically binary classification, which splits patients into two groups. We can convert a regression model into a classification model by employing a decision threshold. The decision threshold,

(tau), is a number between 0 and 1 that can be used to split the risk estimates into two discrete categories. For example we set could set

for the diabetes model mentioned above and say that all risk estimates greater than

correspond to a high-risk of developing diabetes (

). So a decision threshold can be used to transform the risk estimates into predicted labels.

Most of the ML systems used in clinical practice use a model, inputs, and outputs in a manner similar to what we’ve discussed. For example the Epic Sepsis Model can be thought of in these terms. Every 15 minutes the model receives input information, summarizing key fields from the EHR (such as vital signs, lab values, and medication orders). The model then does some basic math (you could do the math on a calculator if you were very patient) and returns a value between 0 and 100. These output values are then compared against a decision threshold and if the patient’s output is greater than the decision threshold (e.g., Michigan uses 6) then something happens (like paging a nurse about the patient being high risk). [2]

Understanding the components of ML models is important because it helps to demystify the functioning of the models and the overall process. There may be black boxes involved, but the input and outputs flanking the model should be familiar to physicians. In the coming post we will discuss how ML models are built. This will then eventually be followed by a discussion of how ML models are deployed.

Erkin

Go ÖN Home

Bibliography

- Mitchell, T.M., Machine Learning. McGraw-Hill series in computer science. 1997, New York: McGraw-Hill. xvii, 414 p.

- Wong, A., et al., External Validation of a Widely Implemented Proprietary Sepsis Prediction Model in Hospitalized Patients. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2021.

Footnotes

-

Note ML is not a monolith and there are many different techniques that fall under the general umbrella of ML and I may cover some of the different types of ML in another post (e.g. unsupervised and reinforcement learning). ↩